By: AbdelAziz Akram, Ph.D.

Researcher, alTaraqi Center

Abstract

In a climate of invading globalization, intersecting interests between multi-national holdings and increasing power of industrial monopolies and oscillating government regulations, think tanks play an essential role of spreading awareness, advocating judicious public policy and helping societies develop and prosper. The developing regions in the world, and particularly the politically unstable MENA region, are, more than any other regions and more than any time before, in need for such organizations. However, the image of certain Western major think tanks has been tarnished recently by funding scandals and political entanglements with often unpopular lobbyists. These particular cases need to be carefully considered when in the process of establishing and/or revamping think tanks in a future democratic, robust and modern Arab world.

Introduction

Mindful observers submit that “the only constant is… change”. Think tanks understand accurately the philosophical construction of this axiom, and the repercussions of such ancient, yet always applicable, wisdom. Accordingly, think tanks have imposed indisputably their prominence and their influence through the role they play in this era of paramount challenges, changes and unstoppably accelerating developments in the arenas of social policy, political strategy, and the fields of economics, military, environment, technology, and culture. As explained in the first part of this series of papers, think tanks perform their responsibilities and pay their monthly bills by various chores related to progressive research, challenging advocacy and questionable lobbyism. The value, morality and ethicality of these activities vary as functions of fields of action, time, location, actors/recipients, and more particularly stakeholders and funding groups [1] .

More explicitly put, established think tanks have been found to either empower the democratic space by conducting policy research and facilitating fair public dialogue and critical debate, or to the contrary and fortunately at a lesser scale, undermine democracy by pushing policies favored by powerful corporate interests, and often not in the direct benefit of the general public [2].

As to the emergent countries, the urgent launching and developing of think tanks appear to be unequivocally necessary to attempt to reach democratic stability, solid human development and optimal economic growth[3] [4]. However, experts and observers pull the alarm and warn against the similar conundrum faced by the developed world, i.e. possible manipulations and pressures, exerted by big corporations, private financiers and other shadowy, and possibly foreign, providers on the operations and management of those advocacy institutions [1] [5].

In an attempt to curtail the role of think tanks according to the expectations of, particularly, the MENA countries and within their civilizational values, the author addresses the following two aspects that need to be considered and critically debated, once the basic outcomes of think tanks are understood:

- The need for think tanks contribution in the younger/future democracies; and

- The “sour-and-sweet” reality of think tanks in the developed countries.

THINK TANK’s ROLE – OUTCOMES

Before considering those two points, let us first explicitly describe the day-to-day activities of think tanks and the effectiveness thereof.

To measure their success or failure, economic institutions, companies and academic organizations, in general, focus on output measurements, such as the quantity of finished products, grants/funding earned, or the number of students attending a university. That is what generally provides value to their stakeholders and helps them evaluate whether the institutions or the companies perform and grow efficiently and effectively, or to the contrary, whether they fail in their missions.

Think tanks, which are generally non-profit organizations, can also be gauged by focusing on the number of distributed books, published reports, held conferences, and managed programs [6]. However, these aspects cannot be the only accurate measures for this type of institutions. What about their success in informing about or advocating for public policy? Should the policy makers refuse to accept the think tanks recommendation, would that be considered as a negative outcome, knowing that the recommendations in question still bring more options to the table and increase the quality and level of the policy debate? Gauging think tanks outcomes, especially by leaders and funders, is clearly not a straightforward task, but it can help define more precisely their tangible mission [7].

Think Tanks, and their equivalent NGOs, produce a combination of different products and services, of which: research, education and advocacy are the most recognized, as presented here above and in the first part of this series of papers. However, a fourth category of products and services, usually attributed to “Do Tanks” and non-ideological non-profit institutions, consists of actions such as: providing small-loans, installing water purification systems, and other similar endeavors. Defending victims of unjust government persecution and/or hindering and paralyzing regulations, or more simply helping edit/draft a law or major document, also qualify under this fourth category. Finally, a fifth category can be the power of networking and connecting researchers, thinkers, experts and donors with beneficiaries in the government and/or public arenas [6].

With such diversity, it is natural to end up with a wide spectrum of outcome measurements, which help reveal to the interested readers and researchers the true nature and impact of think tanks. These measurements, although applicable predominantly to the developed countries with their modern and democratic institutions, the openness of their markets and the transparency of their judicial environments, can also be utilized by the developing regions which anticipate and look forward for a future of stable, strong and democratic institutions. Think tanks measurements can be summarized as follows [6][8]:

- Citations of their products in the legislative bills and laws;

- Number of congressional testimonies, considered as valuable inputs and/or endorsements;

- Improvements in think tank’s generated major indices (such as the economic freedom indices produced by the Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation, the Doing Business Index prepared by the World Bank and IFC, the Global Competitiveness Index, and others);

- Economic impact generated through a public policy proposal made by an institute (for ex. increased transparency resulting from more simple tax structures such as a flat tax, massive creation of capital by improving property titles such as the Peruvian experience, or huge reductions in interest rates resulting from dollarization as in the Salvadorian case);

- The number of donors and contributions raised or disbursed to other organizations such as religious institutions, social/cultural associations, private schools, and other mediating societies (This outcome measures particularly well how a think tank becomes a relevant part of civil society, acting as a resourceful buffer between the state and the individual. The continuity and stability of such supported independent organizations is viewed as a healthy outcome);

- Number, quality, and acceptance rate of applicants to attend programs or to work for the institute (Think tanks can measure their tangible educational programs similarly to the universities); and

- Media appearances and coverage of the think tanks in public, in addition to the expert debates across major news outlets, TV, radio or newspapers. To this point, we can also associate the think tank’s impact via the social media (for ex., using Facebook, YouTube and Tweeter traffic as statistical measures. Think tanks compete with other educational NGOs: for example, the Institute for Humane Studies’ series of short educational videos, viewed more than 12 million times, competes with Khan Academy’s online classes on topics ranging from economics, to American civics and political history).

Alternative measurable outcomes associated with think tanks activities can be summarized as follows:

- stopping a spending project in congress or a tax increase, or improving the cost-efficiency of a government (For ex. Pioneer Institute conducts a yearly “Better government competition” [9] from which winning policy proposals have already generated measurable outcomes, saving hundreds of millions to taxpayers), or

- pushing the “other side” to generate wasteful spending that can be estimated: Citing the example of the “Star wars” program during the Reagan administration that made the former Soviet Union overspend, some think tanks submit that their work can make the enemies of free enterprise waste precious funds, which helps reducing their activities and hostile belligerence.

All these outcomes funnel down to one specific measurement that think tanks accept as an exclusive gauging and success-measuring factor: “policy impact”.

Policy impact is defined differently by the experts. One way to define it is from the perspective of funders and their projects. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines impact as “improved health outcomes achieved”. The Department for International Development (DFID) defines it as “the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy”. Finally, the European Commission describes impact as “all the changes which are expected to happen due to the implementation and application of a given policy option/intervention”. Several organizations/institutes have defined policy impact based on their own missions or goals and then have implemented appropriate but complex methods and algorithms to measure it. It would be too technical to describe further the different types of policy impact in such an introductory paper. However, it is worth noting that, under a prism of diverse appraisals, experts categorize such impact as academic or non-academic, intended or unintended, foreseen or unforeseen. Most researchers also focus on the extent of the policy benefits, i.e. broad or narrow, and the cost for their implementation. Some impacts are classified based on time, which could be a short-term individual impact or a long-term collective impact. More can be found in Ravichander et al.’s reference [8].

The Think Tanks Existential crisis:

The wisdom “We’re nothing more or less than what we choose to reveal” applies dramatically well to several think tanks in the world, given their hidden agendas, obscure funding and lack of management transparency.

To emphasize the might that think tanks enjoy in the Western world, a prominent American politician, Jim DeMint, was asked why he had given up his seat in the US Senate to become president of the Heritage Foundation, a notorious conservative think tank in Washington DC that is having a major influence on Trump’s administration [10]. He replied that the new job would give him greater influence on politics and policymaking than his elected office had. Would such powerful influence and outreach be healthy for the public interest, and for the future existence of think tanks themselves?

Experts diverge on the nature of this influence and its corruptive/toxicity level. While many, such as Dr. James McGann, a think tanks expert, defend that think tanks are beneficial for democracy through enriching the democratic space by conducting policy research, developing policy options, facilitating dialogue between diverse stakeholder groups, and stimulating public debates, regardless of their ideological agendas, others, such as British editorialist, George Monbiot, argue that several of these organizations have become primarily lobbying groups in disguise… that they undermine democracy by pushing policies favored by the powerful corporate interests who bankroll them. In a donor-driven marketplace of ideas, the think tank sector as a whole only serves to further tilt the playing field in favor of the rich, according to Mr. Monbiot [1][5].

Think tanks are all about influence. They are not, generally, neutral when undertaking research and offering advice. They present themselves as neutral academics. However, it is now established that domestic or foreign funders do not grant capitals without a return, without a pay-back price.

Many hidden-funding scandals have been uncovered over the past years between tobacco, petroleum or armament industries, to name a few, and their lobbying think tanks. Nevertheless, the heavy-media appears reluctant to disclose and encourage the debate about such a lack of transparency issue. The reasons can be diverse, even though it might be easy to the common reader to imagine the connection between many of those media organs and the implicated funders.

Fortunately, many research organizations and think tanks, and in an effort to protect the constructive reputation built over the decades by most of these thinking institutions, have started designing and developing a plethora of initiatives, such as “Transparify”, to encourage the think tanks to opt for credibility by choosing transparency, disclosing their funding/donation sources and expenditures [11]. “Transparify” challenges the media outlets, the academic researchers and the decision-makers to distinguish legitimate policy voices, while isolating dubious sources of ‘expertise’. By doing so, the initiative hopes to spark a nuanced debate about the types of think tanks that deserve to have an influence on democratic politics, and simultaneously calls to avoid sound-bites and policy prescriptions produced by opaque organizations of questionable intellectual independence and integrity.

The author hopes that the readers and the interested researchers consider such verification mechanics, when considering launching, developing and/or simply cooperating with think tanks in their respective emergent regions.

Despite the aforementioned warnings, it is undoubtedly clear that the existence and contribution of thinking organizations to the MENA region are key catalysts to the development and stabilization thereof, more particularly given the recent developments with/after the Arab-spring and its respective counter-revolutions,

Think Tanks in the Developing Countries

There is a desperate need for think tanks in developing countries to either support their democratic governments, or in the still-struggling regions, counter-balance the influence of the corrupt and/or failing and deceptive governments.

To address the former case, it is worth noting that in the increasingly complex, interdependent, and globalization-prone world, governments and individual policy-makers all across the world, and especially in the developing MENA regions, face (or will have to face) the common problem of how best to bring expert knowledge to bear in governmental decision-making. Policymakers need basic information about the world they deal with, the societies they govern, the performance of their current policies, their possible alternatives, and their approximate costs and related statistics [12]. However, few developing countries have adequate policy research institutes and resources to help address these challenges. Instead, and when not improvising and/or ineptly imposing unsound policies, their governments have usually to rely on policy ideas imported from abroad -often from foreign think tanks, research centers and consultancy groups to impose external agendas [13].

To remedy to this situation, new or more local think tanks have to be developed and launched over the developing world!

The data collected by world research institutions on think tanks, show that there has been a steady increase in the number of think tanks in the developing countries, and a gradual increase in their engagement with the government, with a relatively slower growth in the MENA region, that will be addressed singularly with more interest in the following paragraph [14]. Under the impulse of some international and/or regional initiatives, the think tanks numbers and their growth, around the world, appear to get some strength [15]. More positive data shows that such a momentum is even forcing several ministries, in South-Eastern Asia countries (like India and China), in South-American countries (like Brazil and Argentina), in African countries (like in South Africa and Ivory Coast), and in the MENA region (like in Turkey, Tunisia and Egypt) to actively engage with their national and local think tanks for their expertise and solicit inputs for framing and implementing policy [3] [4]. Many instances have been also witnessed where governments even have started to rely on think tanks for both short-term analyses as well as long-term studies. Away from the government arena, businesses around the developing countries have begun investing in and establishing their own thinking institutions.

All these developments yielded several, and contrasted illustrations of the important role that started to be played by think tanks in shaping policy in various disciplines across these regions. These include for ex. India’s nuclear energy policies, Malaysia’s economic reforms, Brazil’s environment protection, climate and low carbon policies, etc. However, it is clear for the experts that developing countries have still a long path before reaching an impact, a degree of efficiency, and standards similar to their counterparts in North America and Europe.

Think Tanks in the Arab World

Observers affirm that the democratic environment, such as the one in the US for example, has constituted the best beacon for developing strong and successful think tanks [12]. In contract, it is also recognized that the political difficulties and the civil liberties deficiencies in the developing countries make it tedious to consolidate the process of political reform, at a time when progress towards democratization is uncertain.

In non-democratic regimes, such as in the Arab countries for ex., restrictions on freedom of expression have historically not enabled free and efficient communication of knowledge, nor have they facilitated constructive exchanges of opinions within and between the respective societies. For a long time, think tanks were repressed or co-opted by authoritarian regimes. At best, they have remained politically-neutral and/or provided very limited expert views on a set of policy proposals or reforms introduced by the regimes in place. However, these institutions have unfortunately not been able to contribute to policy formulation. Moreover, seldom could these think tanks play a role in constructing the political elite’s intellectual discourse [3].

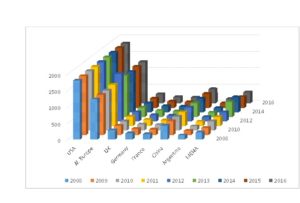

A simple comparison between the total numbers of think tanks in the MENA region and the developed world (see table 1 below) portrays clearly a dreadful picture confirming the vast gap and the increasing delay to make up between the aggregate numbers of such organizations in both regions. It can be easily noticed that, in 2016, the total number of think tanks per million of citizens is less than 1 across the MENA countries (with a total population of about 370 million people), and is consistently and significantly smaller than that in Argentina (population of about 43 million people, and a density of think tanks of about 3 per million),

| Country | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Total | 5465 | 6305 | 6480 | 6545 | 6603 | 6826 | 6618 | 6846 | 6846 |

| USA | 1777 | 1805 | 1816 | 1815 | 1823 | 1828 | 1830 | 1835 | 1835 |

| W. Europe | 1208 | 1233 | 1222 | 1258 | 1457 | 1267 | 1244 | 1267 | 1267 |

| UK | 283 | 285 | 278 | 286 | 288 | 287 | 287 | 288 | 288 |

| Germany | 186 | 190 | 191 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 195 | 195 |

| France | 165 | 168 | 176 | 176 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 180 | 180 |

| China | 74 | 428 | 425 | 425 | 429 | 426 | 429 | 435 | 435 |

| Argentina | 122 | 132 | 131 | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | 138 | 138 |

| S. Africa | 78 | 84 | 85 | 85 | 86 | 88 | 87 | 86 | 86 |

| Israel | 48 | 52 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 58 | 58 |

| MENA | 170 | 221 | 279 | 275 | 285 | 456 | 465 | 340 | 340 |

| Iran | 12 | 24 | 32 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 59 | 59 |

| Iraq | 15 | 28 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 43 | 42 | 31 | 31 |

| Egypt | 23 | 29 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 55 | 57 | 35 | 35 |

| Turkey | 21 | 21 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 32 | 32 |

| Tunisia | 8 | 9 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 39 | 38 | 18 | 18 |

| Algeria | 4 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 9 |

| Morocco | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 30 | 33 | 15 | 15 |

Table 1. The evolution of the number of think tanks over the World and MENA [14].

South Africa (population of about 54 million people, and a density of think tanks of about 1.6 per million), and Israel (population of about 9 million people, i.e. about 2.5% of the MENA population, and a density of about 6.5).

The MENA data are also insignificant when compared to the Western countries (Ex., USA with a density of 6, Western EU with a density of 3); See Fig. 1. Observers can also notice the limited fields within which the MENA think tanks focus and perform their activities, compared to their neighbors’ counterparts. Needless to submit here that the close organic ties and the strong cooperation between the Hebrew state and their Western allies can provide some explanation of such contrast in the quantity and the quality of the think tanks in the compared cases.

Fig. 1: Yearly variations of the number of think tanks per region/country; data collected from reports in [14] .

Fig. 1: Yearly variations of the number of think tanks per region/country; data collected from reports in [14] .

This being said, things are changing. Since, the first Arab think tank, i.e. Al Ahram Center (aka ACPSS), officially launched in Egypt in 1968, the last few decades witnessed the leadership and intelligentsia of many countries, such as in Turkey, in the race to build up a modern industry of thinking and strategizing in the region, helped by their strengthening economies and the continuous healing/strengthening of their human development indices. The most noticed activities have been focused on organizing seminars and conferences, publishing books, magazines and bulletins, especially with the ever-increasing availability of the internet and its powerful and relatively affordable outreach capabilities (consider for ex. “virtual think tanks”, such as Dr. Y. El Qaradawi’s Islam Online, which is mainly a political research unit).

The fields of action of such MENA organizations were mainly around regional affairs studies, private entrepreneurship advising, micro-economics programs, and interfaith dialog initiatives.

Examples of reputable (non-virtual) Arab think tanks, in addition to ACPSS introduced here above, are as follows:

- the Center for Arab Unity Studies (Lebanon, 1975), of which the published books are used as textbooks in the region, and whose members have initially dedicated their research towards all aspects of Arab societies, including Arab nationalism and Arab unity movement, away from any local politics. However, and more recently, the Center has performed single-country studies, such as the Palestinian cause, the Algerian crisis and Lebanon reconstruction.

- The Rand-Qatar Policy Institute (Qatar, 2003), the Brookings Doha Center (Qatar, 2007), and the Gulf Research Center (UAE, 2007) which represents the emergence of a trend of joint think tanks, co-sponsored by Western partners, such as Rand Corp., The Brookings Institution., and the London-based IISS, respectively. These Gulf institutions take advantage of the astronomical wealth availability in the region, and span their activities across the fields of national and regional policy making, education development, economics, military, social and cultural affairs.

- The other parts of the MENA region (See Fig. 2), such as in Yemen, Palestine, Jordan, and the North-African Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, offer also think tanks with very similar profiles as their counterparts in the Gulf countries, but with noticeably less resources, partnerships and funding, and more restrictions, political chasms and research environment insecurity.

Fig. 2: Yearly variations of the number of think tanks in some MENA/Arab countries of interest and their comparison with those in France and Israel ; data collected from reports in [14].

Fig. 2: Yearly variations of the number of think tanks in some MENA/Arab countries of interest and their comparison with those in France and Israel ; data collected from reports in [14].

- Finally, countries such as Iraq, Iran and Turkey have shown a strong determination in joining the club of the countries with increasing numbers of think-tanks, the activities of which touch all the sectors that are vital to the development of their respective countries. The most recent succession of developments in the region, such as the invasion of Iraq, the civil war in Syria and the terrorism expansion across the borders, has clearly negatively impacted the momentum of the healthy think tank programs of the concerned countries and their neighbors, despite all the initial expectations and the strong resolve demonstrated by the interested members.

Another episode in the recent history of the region needs to be highlighted. With the advent of the Arab uprisings and the transformation of political regimes in the region that promised a larger space for individual liberties and free expression, it was expected to see think tanks and policy research institutes flourishing and devoting their efforts toward creating a pro-democracy and pro-dialogue environment. A series of new initiatives had emerged from thriving regional civil societies in order to reconstruct the “battle of ideas” in the fast-changing political landscapes. Such efforts could have upheld some of the progress made by the revolutionary forces, especially in Tunisia, the cradle of the so called Arab Spring.

Let us remind that the authoritarian regimes across the Arab worlds had exceled in shackling, and even annihilating, all initiatives for independent political research that could reveal the non-democratic and often illegal, military coups, pressures and manipulations practiced on their respective civil societies. The desperately needed independent research surely could untangle the stronghold position of the regimes on the reign of power in the different countries. Hence, one can easily understand the destructive control chosen by the regimes towards such beacons of intellectual activism. This is a reminder that the need for think tanks to rebuild the intellectual foundations, damaged by the authoritarian regimes, is a must, and a necessary step to reposition the Arab countries on the trajectory towards development, civilization and prosperity.

Expectations from the MENA’s Think Tanks

To reach such an audacious goal, Arab think tanks need to learn from their Western counterpart, and strategize their actions around the three following principal tasks[3]:

- Informing: with a culture of “thinking awakening”, think tanks need to connect new political discourses with the general public and the civil society, and promote a “culture of informed citizenship” in initiatives that can produce relevant information on new government structures, policies and reforms.

- Convening: This is a crucial mission for the think tanks in the region, as they need to act as connectors within their societies that undergo political turmoil and transformations. Initiatives should help gathering pro-democracy factors and reinforce dialogue between political factions. In so doing, think tanks convene political actors with diverse – and often diverging – views on key topics of the reform agenda, which provides an opportunity for outlining inclusive policy proposals. Other initiatives should aim at overcoming the lack of connections between civil society actors and the new political leaders, by promoting the think tanks relationship with government officials, reaching out to the media and interacting with the people. In this way, they can provide an added component of legitimacy and strength to the new democratically formed political systems. While their actions towards the population and the media can contribute to building a better democratic culture, their actions towards the government are based on the need to challenge the deep roots of authoritarian states and to move from a culture of repression to a democratic culture within state administrations. Examples can already be reviewed [16]. Palthink for Strategic Studies, a new Gaza-based think tank that defines itself as a “think and do tank”, bringing together diverse Palestinian actors in order to “stimulate and inspire rational public discussions around core issues that concern the Palestinians and the region”. In October 2012, Palthink hosted an exchange of views between Khaled Meshaal, head of the Political Office of Hamas, and non-Hamas actors in Gaza. Similarly, the Brookings Doha Centre, is implementing the “Transitions Dialogue” program to “bring together mainstream Islamists, Salafis, liberals and leftists, along with US and European officials, to exchange ideas, develop consensus, and forge new understandings in a rapidly changing political environment”.

- Advocacy: To achieve political impact, think tanks need to suggest policy solutions. This goes beyond the generation of information and research and, in the context of Arab transitions, often translates into actions aimed at the reinforcement of democratic systems in post-revolutionary scenarios, despite all the difficulties and risks of alienation if deeply divided societies. As an example, The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, for instance, carries out advocacy activities and combines the publication of in-depth reports and testimonies on the human rights situation in Egypt with the ‘development, proposal and promotion of policies, legislations and constitutional amendments’.

This being said, lessons have to be learned from the young experiences that have already taken place in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia. In those countries, the first think tanks that formed or that just morphed with the new environment after the Arab Spring revolution either were the first ones to participate into the counter-revolution or were rapidly stalled by it and ended up caving in to the sour reality. A better vetting of the think tanks members and a more solid preparation is therefore needed for stronger and more dedicated institutions in the ever-increasing complexity of the local, regional and international political environments.

In the upcoming and third part of this series of paper, we will address the building of think tanks and the necessary ingredients needed for their success.

References:

[1] “Think tanks, evidence and policy: democratic players or clandestine lobbyists?”, T. Bruckner (2017).

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/08/us/politics/think-tanks-research-and-corporate-lobbying.html?_r=2

[3] “The role of think tanks in Arab transitions”, Pol Morillas (2013).

[4] “Arab and American Think Tanks: New Possibilities for Cooperation? New Engines for Reform?”, E. Ibrahim, (THE BROOKINGS PROJECT ON U.S. POLICY TOWARDS THE ISLAMIC WORLD) (2004).

[5] http://www.monbiot.com/2013/11/29/hidden-interests/ , http://www.monbiot.com/2011/09/12/think-of-a-tank/ … and the author’s columns at The Guardian.

[6] “15 Ways Of Measuring Think Tank Policy Outcomes” by A. Chafuen, Forbes, Apr. 2013.

[7] “Think Tank Effectiveness- An Outsider View” by N. Krishna, On think Tanks, Dec. 2014.

[8] ”Policy Impact: A think tank’s perspective “ by A Ravichander et al., On Think Tanks, Nov. 2016.

[9] http://pioneerinstitute.org/better-government-competition/

[10] http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/06/politics/donald-trump-heritage-foundation-transition/

[11] http://www.transparify.org/

[12] “Think Tanks and the Transnationalization of Foreign Policy” by J. McGann, The Quarterly Journal, Mar. 2013.

[13] “Setting up a think-tank step-by-step” by E. Mendizabal, On Think Tanks, Jun. 2016.

[14] 2008-2016 Global Go To Think Tank Index Reports, J. McGann; can be retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/?utm_source=repository.upenn.edu%2Fthink_tanks%2F2&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

[15] See “Initiative Think Tank” Program, initiated by the Canadian Government in helping to strengthen 43 policy research institutions in 20 developing countries over 10 years through a mix of core funding and support for capacity development.

[16] http://palthink.org/en/?p=808 and http://www.brookings.edu/about/centers/doha/initiatives

[17] https://ommahpost.com/5-questions-explain-the-research-strength-of-the-american-think-tanks/